Petrologists peer into slivers of rock seeking good fortune

Alberta - January 29, 2020Some people read gemstones in pursuit of personal clarity: emeralds, for example, are said to help foretell the future. For a few scientists in Alberta’s oil and gas sector, however, sedimentary rocks will help lead the way.

The “rock readers” in question are known as petrologists. Their job is to study different rocks up close and find clues to an area’s geology and history. Oil and gas companies can use their findings to locate zones for exploration and development.

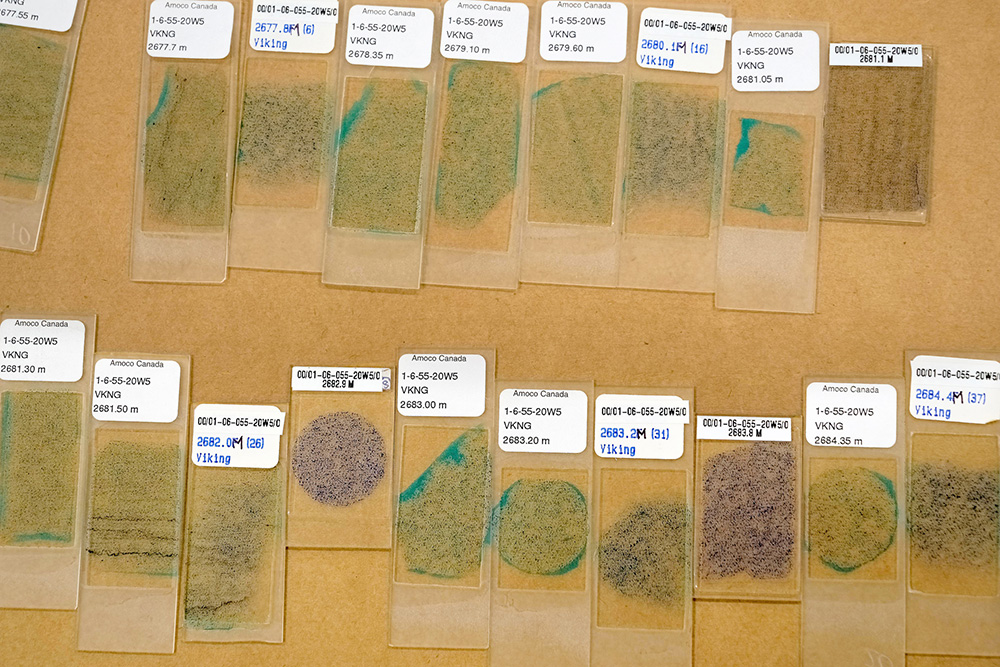

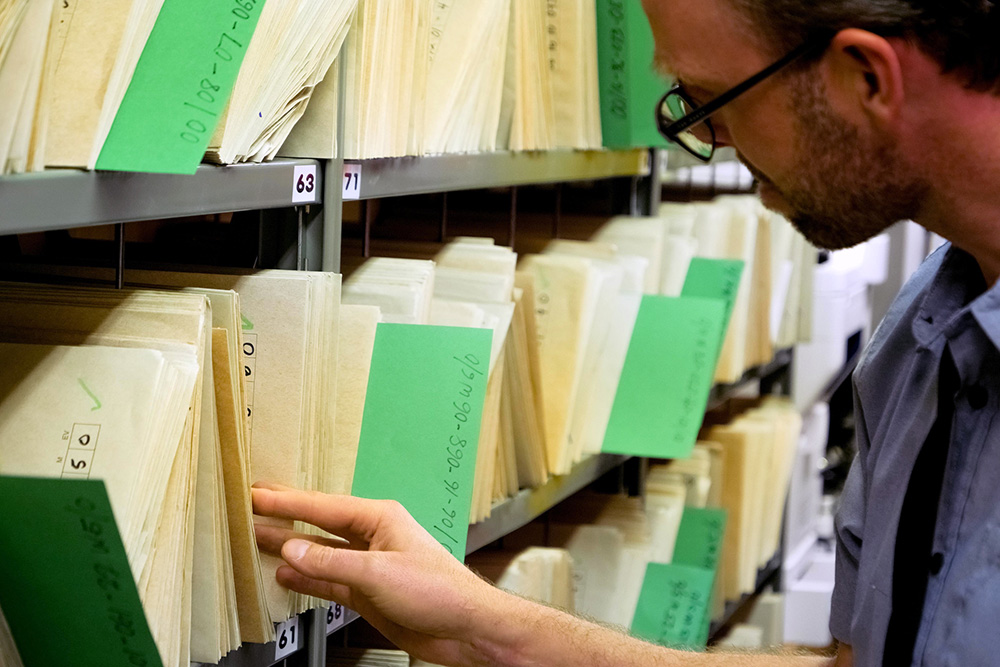

To foresee a potential oil or gas fortune, petrologists use a paper-thin slice of rock known as a “thin section,” which is made from core samples or drill cuttings. The Alberta Energy Regulator’s Core Research Centre (CRC), located in Calgary, provides the largest collection of thin sections in Canada, totalling over 44 000 and counting. With the right technology, petrologists and companies can see exactly what lies beneath the surface.

A single thin section costs about $50 to create, but for many companies the price is worth it. Thin sections can save a lot of time and effort as details about an area’s geology are literally unearthed from a rock sample.

Let’s take a closer look at how a rock reading plays out.

When a petrologist wants to learn more about a specific zone, they will send a rock sample from the zone to a specialized thin section lab, requesting that a slice be removed from it and made into a thin section slide. Lab technicians cut the rock slice and glue it onto a glass slide. The rock sample is then sawed down and polished until it is 0.03-millimetres-thick (thinner than a piece of paper).

Dyes are often added to thin sections to highlight what minerals are present, such as calcite, dolomite, plagioclase, and feldspars. When the slide returns to the petrologist, the dyes will help them determine the mineralogy and gather clues about the zone’s geology. A petrologist’s findings can help guide decisions on energy development, including why, how, and what a company’s next steps should be.

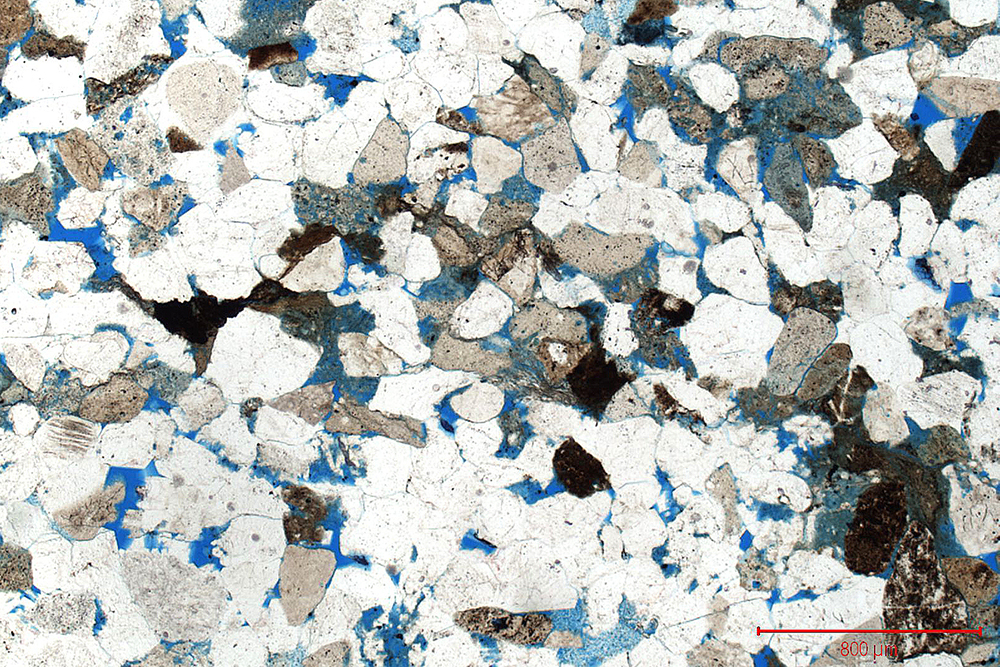

With the right microscope, a thin section can reveal as much as a Google search. Many petrologists use a special petrographic microscope to zoom in to see what the rock is composed of. They may also look for natural fractures and porosity in the rock.

Magnified 32 times, this microscopic view of a thin section provides an up-close look at fine-grained, litharenite sandstone from the Cadotte Formation in Alberta. The stunning minerals seen include quartz and chert, among others. Depending on the rock, thin sections might also reveal fossils.

Anyone who borrows rock samples from the CRC to create thin sections must submit copies of their slides to the CRC for others to use. The CRC adds every thin section to its growing index and library. The centre also provides a petrographic microscope for anyone seeking a closer look.

The CRC’s thin section index is publicly available on the AER's website. Learn more about the CRC and how to visit on aer.ca.

Kara MacInnes, Writer

Luke Spencer, Digital Media